To observe and hold a newborn, is to be reminded of the possibility and potential we all have and hold in this lifetime. Possibilities that we all to often forget or push aside, either for a lack of opportunity, or perhaps simply a lack of courage and dedication to pursue them to their completion.

Potential is a concept that has the ability to both inspire some to great heights, while at the same time frustrate others in their failing efforts. What separates the driven from the frustrated is likely a combination of maturity and humility, for any journey or achievement is filled with repeated difficult efforts. To reach ones potential requires acceptance of the hard work in getting there. In order to understand what is actually potential requires knowing fully what is possible, and with that, what is ideal. It is likely that insights like these none of us will ever truly possess, only grasp at. Regardless we still have to try, and with that decide what one should aim for in this lifetime.

Thus, one has to ask some very difficult questions.

What makes a well-developed, well-rounded individual? What are the far reaches of human development that we all should esteem and strive for? With that, what is the minimum standard we all should ask of ourselves? What is our commonly held human potential?

Often times the culture and society we exist in dictates the answers to these questions, but relying solely on that is a dangerous thing. A good example of why is observed by witnessing the fleeting and frivolous values of fashion, magazine headlines, and reality television stars. Truly, although we as humans are capable of incredible things, we are also all heavily susceptible to buffoonery. It is good to search for something beyond the current values of the present culture, and to do that it is necessary to look at the possibilities most all of us enter into this world with, and perhaps the possibilities we should better pursue in our precious time spent here.

There are three words that make up the title of this article, and within that two concepts; Cultivation and Kinesthetic Intelligence. Now, broad and sweeping statement are rarely accurate, but sometimes they are all one has. Arguably these two concepts are values that have been by and large lost in our present culture, and deserve attention by anyone looking to achieve not only health, but over all strength and durability.

NORMAL HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

We enter this life all with our own unique presets and proclivities, and if we are blessed with the right combination of nurturing and exposure we just may be able to develop from them incredible talents. Each of us hold our own unique potential.

However unique and individual we may all be, the first few years of human development are strikingly predictable. All of us leave the womb neurologically immature, unable to manage much in the gravity field beyond breathing. From there we all learn to lift our head, arms and legs slowly but surely in a predictable sequence and timeframe. All of us, in order to reach the upright posture of mankind, must roll over before crawling, and crawl before we walk. The order is generally set, and the fundamentals of one stage must be mastered before being able to smoothly move on to the next. So predictable is our development that physical abilities (ranging from developmental posture, grasping ability, head control, and eye tracking) are assessed in a developing newborn to ensure there are no signs of cognitive or attentional impairments (1). In this way, physical ability and development is directly correlated with cognitive ability and development in the first years of life.

Strangely though, physical development is considered in our medical culture to be a sign of cognitive development in young children only. Presently, in our modern world, we have available numerous metrics of intelligence in adults, with the vast majority of them assessing verbal/language skills and mathematical-logical reasoning (2). In the developing child, verbal and language skills are understandably limited, which is why varying aspects of movement is used instead. One needs sufficient cognition to engage their environment and problem solve navigating it with their body, and in doing do master motor skills in a timely manner. In early childhood sufficient motor delay is linked with cognitive delay; the body is merely the extension of the mind housed within. So if this is known to be true in the developing child, what changes in adulthood?

Arguably nothing. The link between activity and cognition exists though throughout the lifespan (3-7), as the acquisition and practice of physical skills is deeply ingrained with intellectual reasoning. Truly, it should not end with childhood. Unfortunately we lack a clear understanding of what one should strive to physically attain in their lifespan. Perhaps it is clouded by the complex variety that make all of us up. After early childhood, development becomes less predictable, perhaps due to do many effecting factors. Like a tree shooting up and spreading outward, the environment we mature in may heavily dictate both the direction and height our branches go. However, just like a tree, it is wise to spread in every direction available, including deep with the earth, rooting ourselves to the ground. Upwards, downwards and out is perhaps our maturation ideal to draw and deviate from.

This requires an understanding of a central point of origin to spread from, and a rich ideal to mature towards. This this is where we return to the question of what dictates our potential.

Although internal motivation may decide whether it is engaged and met, it is possible that what defines an individuals potential is found in the breadth and depth of intelligence they possess. This intelligence is not limited to what can be measured on a multiple choice exam or modern standardized test. This intelligence is the inherited ingenuity that allowed our ancestors to not only survive but attempt to make the world they lived in a better place. History shows us they did not always succeed, but by nature of us all being here in this present time, our ancestors were obviously clever enough to survive and thrive in what ever they encountered.

MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCE THEORY AND WHAT MAKES UP HUMAN POTENTIAL

“All models are wrong, but some are useful”

-George Box

Despite having existed as complex and introspective societal beings for centuries, what makes up general intelligence is still controversially defined (2). With that being said, it can and has been generally described as the ability to both learn from experience and to adapt to and shape the environments one is in (2). That is a summary that works fairly well but lacks the depth that makes us all so nuanced. Having been studied formally in our modern world for over a century, in that time several competing models of human intelligence have arose (2). Although there several presently, one in particular lends itself to modeling the complexity that is a well developed human; multiple intelligence theory.

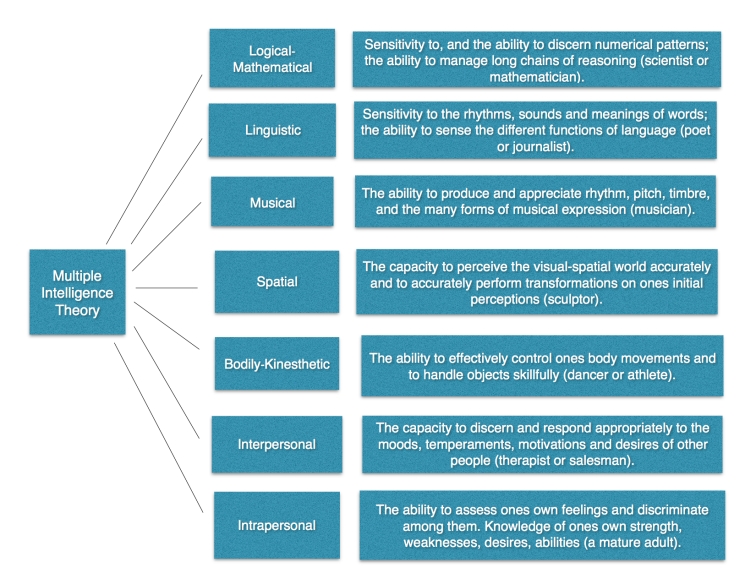

Developed by Howard Gardner, the theory aims to address the multi-modal portions of intelligence that appears present in a typical human being (8, 9). Dissatisfied with both the available theories at the time, as well as the increasing scholastic emphasis on solely verbal and mathematical aptitude, he sought to develop a more encompassing model. Gardner observed that separate psychological processes seem to be involved with different symbol systems commonly encountered in daily life (numerical, language, pictorial, gestural, etc). He also observed that some individuals may be very talented at one form of symbol use and manipulation, but have little carryover to other forms. An excellent example of this is seen in the abilities of autistic savants. In addition, it has been readily observed that with significant brain damage some abilities may be notably compromised, while others completely unaffected. All this combined led Gardner to propose that they may exist multiple forms of independent intelligences within the typical human being, with their inter relationship unknown.

Pouring through the available literature on varying skill sets, Gardner proposed that there exists at least seven distinct intelligences within the human mind. The diagram below gives an effective summary of the seven total parts that comprise multiple intelligence theory.

Here intelligence is defined as the ability to perceive, process and accurately interact or manipulate variables across multiple environments. It is not isolated to what can be easily measured on a multiple choice exam in an academic setting, but looks at the many skills that make up an effective human being as they interact and navigate the world at large. Arguably this model defines the multi-layered intelligence that makes up what is a complex and mature human being.

What perhaps makes this theory so beneficial is that it speaks to much of what one observes in their daily life; each of us possesses diverse skill sets, some of which are more developed than others, and some of which are more useful in some situations more than others. One could have a high level of academic intelligence, but such poor interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligence that they are effective at only a handful of things in their daily life. They are good with things but not necessarily people. On the other hand, one may not have thrived in an academic setting, but blossomed to become an talented athlete/dancer or artist. They are good at abstract things. Others, regardless of their own abilities, may become a great teacher of a variety of skills they themselves are only moderately talented at. They are good with people.

In this way, despite our modern educational systems emphasis on verbal and mathematical abilities, one cannot weight one form of intelligence over the other. Success in life is rewarded to those who not only have cultivated greatness in some particular pursuit, but at the same time a balance in their intellect in order to attain and maintain it. All of these forms of intelligence are worthwhile cultivating, and with that we turn to one intelligence in particular; that of the body.

KINESTHETIC INTELLIGENCE AND THE IDEAL OF MOVEMENT MATURITY

Often times parents will marvel in awe at the graceful movements of their children. Typically in our modern day this is because their are observing the child run with abandon, squat with ease to the floor, or climb a tree or playset without hesitation. Yet the source of admiration is often not simply out of wonder; often it is because they themselves have not only lost these skills, but failed to ever further their physical abilities beyond.

Just as our intellectual depth, breadth and capacity should far exceed our children (for they have far less life under their belts), our movement capacity and skill set should also far exceed theirs. Movement maturity should not end with graduating high school and no longer being on the seasonal sports team. Games are for playing, and truly all of us should play until the day we leave this earth, but at some point we need to accept the responsibility of an adult and pursue strength and durability. Unfortunately, this is not only uncommon, the idea itself is rarely a thought in the world of today.

Arguably our modern present culture has lost its bodily connection. While the appearance of an athletic body is readily valued and desired, the appreciation of the thoughtful hard work and dedication involved in cultivating such an appearance is not. In many ways though, this is emblematic of our modern society; we want the results without the sacrifice.

However we truly can never have our cake and eat it too. An athletically appearing body is simply the result of regularly challenging it physically in a progressive manner over time, all while eating an appropriate amount of calories to minimize padding. Whether one accepts it or not, our outward physical appearance from a physique point of view is simply a summation of habits, practiced over time to cultivate the result. However, kinesthetic intelligence is not the appearance of an athletic body, but the ability for the body to be athletic and capable.

Kinesthetic intelligence is our grace, coordination and physical capacity. It is our knowledge of where our body sits in its environment, and the where/how to make the effects we desire with it.

Kinesthetic intelligence is speed with precision, power and accuracy. It is the ability to create great force in an instant, and as the next arrives let it go. It is our ability to make real the physical dreams of our minds, the connection of our will to the world around us.

Kinesthetic intelligence is not simply limited to ones capacity in sports endeavors, but a broad ability to exist and flow through our limbs in the way we desire. Just as a high verbal intelligence is seen in an effectively articulate individual, a high degree of kinesthetic intelligence is seen in the dancer moving with poise, power and ease.

This is the bodily connection to the world at large. It is the perception of our five limbs (head-neck, arms and legs) moving about and through their torso with symphonic purpose. After all; the body is an organ of perception, not merely action, and it must accurately know its place in the world at all times. Thus, kinesthetic intelligence is an ability to physically listen not merely effect. It is the body intellect.

Likely, this is cultivated by the majority of us in our modern first world during and through childhood, often times not beyond. For many of us, once we pass adolescence we tend to not typically learn new physical activities unless we individually pursue them. For most adults the last time they learned a novel physical task was learning to drive a car. From then on it was simply the fine motor demands of our work days and social lives. As adults many of us become ingrained in habits, and the demands of our careers and family life can take over. With that days and weeks can often go by without a novel physical experience happening. The challenges of our first world are, by large, sedentary.

However some individuals, by the nature of their work, learn new challenging movements all the time. This is seen in the demands of surgeons, performers, artisans, and tradesmen. Their work is of their hands and body, not solely the mind housed within.

Other individuals have cultivated hobbies and physical pursuits that by their nature engage and develop their bodily connection. This is seen in those that enjoy exercise in all its forms, be it rock climbing, hiking, surfing, skiing, yoga, dance, martial arts or strength training.

While regular physical pursuits are important for all us to have, they must not over shadow the intentfull cultivation of a mind-body connection. Truly, this is what exercise in its purest forms is intended to accomplish. It is via formal exercise that one has the chance to both regularly cultivate their bodily intelligence, and practice the habits that will serve them best. With that, one ideally grows and deepens their well of knowledge and understanding with each passing year of their life. By your fortieth, fiftieth year one should better know their hands, feet and limbs better than at twenty. With this in mind, exercise is not only a chance for regular activity but also a regular pursuit of ever evolving movement maturity. Through it one is always learning, deepening, and broadening the body intellect. Through exercise one is always the student, with gravity and mass as teacher. The fluid coordination of physical prowess should be viewed as an intrinsic part of being human, not an isolated event of youth, or a gift of birth for a few. It is ours to develop, and cultivate, each in our own ways in each of our own lifetimes.

Cultivating a strong, able body that our mind readily inhabits is a crucial part of achieving and meeting our overall, not just physical, potential. It requires discipline, the acceptance of limitations, and the intentional study of how one can effectively expand them. These are values that are components of maturity, not just athletic prowess. Arguably our body is the expression of our habits. Its fitness and capacity is not attained by chance, but by both action and inaction repeated day in and out.

Thus, ones strength, endurance and overall conditioning can have far reaching effects on ones kinesthetic intelligence. It is of little worth having aware and coordinated limbs and parts do not have the strength or stamina to either perform or last very long at all. Regardless, the foundation is the movement itself, and cultivation of strength and endurance can only be attained when the fundamental has been gained. This brings us to the necessity of educating the mass culture at large of what makes up a body intelligent.

EDUCATION AND THE PRODUCTION OF INTELLIGENT INDIVIDUALS

“Everyone has a right to education.”

“Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality.”

– Universal Declaration of Human Rights, United Nations

In its broad context, the purpose of formal education could be said to both develop ones potential intelligence, as well as produce individuals capable of engaging and supporting the existing culture and society at large. At the end of their schooling they ideally have the tools to become a productive and contributing member of society.

The problem is that presently, in the United States, we could argue that our educational system does not truly produce well rounded and well developed young adults. A strong statement but it may have credence; when compared to other developed first world countries, the United States is not at the front of the pack.

Every three years the Program for International Student Assessment performs an assessment of reading ability, and math and science literacy of 15 year olds in the developing and developed countries of the world (10). As of 2012 the United States ranked 35th out of 64 countries in mathematics, and 27th in science ability (10). These are sobering statistics for any individual that assumed otherwise. When faced with such reality, it is prudent to ask what the other countries are doing differently.

One striking difference is seen in the volume, frequency and value placed on recess for school children. In the United States, the average amount of recess an elementary school child gets is 27 minutes a school day (11)). In contrast, in Finland the same age group has an average of 75 minutes a school day, and in Japan children receive 10-15 minutes breaks each hour in addition to a longer single recess period (11). It is good to note that Japan and Denmark rank much higher than the United States in math and science; Japan 6th in math and 3rd in science, Finland 11th in math and 4th in science (10). Now, correlation does not necessarily equal causation, but the positive effects of recess on the academic and developmental success cannot be ignored.

It has been well established that regular, daily recess is extremely beneficial for not only a child’s academic performance (12), but their overall emotional, physical and social well being (12, 13). In order for a child to effectively process and learn, there needs to be regular periods of interruption accompanying any period of concentrated interaction (14). Notably this period of interruption is most effective when it is in the form of unstructured breaks, not merely moving to a different cognitive task (14). In fact, there is an abundance of literature demonstrating what any parent, caregiver or teacher has observed since the dawn of time; regular recess, regardless of what is done during it, improves attention and productivity in the classroom (15, 16). These benefits are not exclusive to children, as it has been shown to persist through adolescence and adulthood.

How so?

Along with regularly attaining a good nights sleep (17), regular exercise is one of the more effective methods of improving cognitive function and thus academic performance (3-7). Regardless of age, it has been shown that simply experiencing 15 minutes of moderate intensity activity resulted in immediate improvements in both affect and working memory (4). Fairly help helpful things if one needs to learn something. Beyond its immediate effects on our mental state and capacity, regular exercise and a high level of fitness is also associated with improved general cognitive ability (3), and is even protective against dementia and cognitive decline as we age (18). With this knowledge, one would think that those responsible for educating our youth would emphasize regular, periodic physical activity throughout every school day.

Unfortunately there has been a recent trend in the last few decades of decreasing the time dedicated both to recess and physical education in the United States (12, 19), with some districts implementing a “no recess” policy (20). A survey of 487 schools in the Chicago area indicated not only a stark lack of recess at the elementary level, but only an average of two days a week of physical education (21). Only 18 percent of the schools provided daily recess, and only six percent provided recess for a total of 20 minutes. A stark difference between the other countries listed above. These decreases in time dedicated to unstructured play and physical development are thought to be driven by recent legislation pressuring school districts to meet certain mandates of academic performance via standardized testing. The thought is that more time should be dedicated to academic focus, with recess a distraction to it. Tragically, by myopically reducing this crucial part of what allows us to focus and learn efficiently, school officials have only challenged themselves further to meet their pressured goals. Just as there are more portions of intelligence than the two easily measured academic parts (mathematical and language), there is more than one manner in which individuals learn and develop. For more than some, the need to regularly get out of their head and into their body is a critical part of intellectual digestion.

With all of this, one really can only hold a societal or collegiate form of schooling responsible for so many things. Plenty of learning is done outside the school walls and college campus, and eventually each individual ideally graduates from what ever level of education they attain and moves on into the world at large. From there forward, their development is entirely their own to undertake. Truly we, each as an individuals, are responsible for our own lifelong investment in perpetual learning and maturation. It is here, within this individual responsibility, that we arrive at the second concept of this article.

CULTIVATION (THAT WHICH CANNOT BE RUSHED OR BRUSHED ASIDE)

In our current and present culture of instant gratification, instant mastery, and the belief that expertise is something that can be achieved through short cuts, the concept of cultivation is one that has been nearly lost.

Arguably, nothing in this life is permanent or guaranteed. As the saying goes, the only constant is change. The value of cultivation understands this and aims to engage life as a process, one that is always evolving, and requires constant, patient engagement. Perhaps to best understand it, we should look at the areas that the term cultivation is most often referred to; farming and horticulture. As Steven Covey articulated well in his extremely influential book (22), you cannot wait until the last minute on the farm. For the harvest to even come, one must do the necessary work prior, and with that understand how to do the work well. When the harvest has arrived, it cannot be left for later, it must be reaped at the necessary time. Neither to early or to late will not suffice; it must be done exactly as necessary.

Our body and mind, with all its far reaching potentials, is much like a farm. To make it fruitful and productive, it will take much more than midnight rush left to the last minute. In reaching out towards out potentials, one must accept the necessity of planning, introspection, reflection, repeated attempts, consultation with those who have more knowledge or experience, and most significantly a commitment to a long term vision.

The concept of cultivation understands that the grass is not always greener on the other side, that often times one has to do the work of making the grass they are already on as green as they want it to be. Greatness takes work, and it cannot be done for anything other than the enjoyment of the process. This is seen in the process of becoming a master gardner, sculptor, woodworker, professional musician, a surgeon, or an accomplished martial artist. Their work is an ongoing process, and to even achieve proficiency, much less mastery, it is well recognized the sacrifice of time and practice required. Furthermore, it is understood that if the practice is neglected, the skills will become rusty and diminish. Any skill, to be maintained, must be practiced. Just like learning a foreign language at one point in our lives does not guarantee proficiency will be held, physical prowess must be used and well oiled to be kept. Like it or not we all are in constant flowing motion, and if not used a skill will often fade.

Cultivation is an investment, not merely a deal. It is a slow, stewed and often stirred process.

Cultivation is an act repeated with attention to the detail. It cannot be rushed, saved for later, or allowed to be an after thought.

Cultivation is not the result of half efforts, of good intentions without follow through, or of outcomes left to luck. It involves studying and accepting the natural timelines and processes of an endeavor, humbly committing to them, not attempting to cut corners or skip steps.

Cultivation is a recognition that we get what we train, practice, and repeat.

When applied to ones physical body, its capacity, and indeed its kinesthetic intelligence, the connection should now be fairly clear. Our bodies in its many systems are in a constant state of adaptation, and it is up to us to choose what direction this adaptation will travel. The way of the weekend warrior, squeezing in intense activity around a week of sedentary living, will achieve little good. We are the summation of habits, day in and out, and like anything precious in this lifetime, most things will have to be kept in order to be owned.

SHOULDERING THE LOAD, HOLDING THE RESPONSIBILITY

Here we must return to that elusive concept of potential. Unique to us all, it is akin to a ripple building to a tidal wave, but it is a ripple that is moved along actively. More often than not, it will have to be pushed to move and grow.

There are things in life that can only be a trained and maintained through attentive practice and repetition. Arguably, these things consist of the majority that makes up our time on this earth. Nothing is permanent, and anything of value will take intention in order to keep present and healthy in our lives. Each of us enters this world with innate talents that hopefully are allowed to blossom and develop throughout our lifetimes. With intense development in one area, very often, deficits coincide in others. Arguably our present academic world rewards those who have a high level of math and social intelligence, and yet the world we all inhabits requires us to to possess far more than that. Although we may desire or need a level of greatness in a certain area, we will need to maintain competency in all the rest for the best chance at success.

Unfortunately, well rounded and developed adults are not what constitutes the majority. This is seen in problems managers and supervisors face in the current workplace. Their employees may possess some select concrete knowledge necessary for their job, but often times lack in their ability to problem solve, be creative, or effectively interact in the face of challenge and conflict (23). In short, they lack the well rounded intelligence to navigate the challenges of our world.

Truly, this is a cultural problem. For the situation to improve, society must value not only the vitality of the body (the cultivation of attaining and maintaining it in all its potential), but also the multiple facets of a fully developed human being. This requires society to understand and respect that a skill must be maintained, that an ability cannot be owned if it is left on a mantle to admire once attained. Such is the nature of so many preventable and costly medical conditions, and if the exploding prevalence of adult onset diabetes is any indication(24, 25), our society as a whole lacks a long term commitment to ourselves. but like flossing, all require an active and conscious approach.

Intelligence and physical capacity, much like the nature of adult onset diabetes and despite what some may resign themselves to, can always be improved upon. Our bodies and minds are always adapting, and truly we are malleable both physically and intellectually until our last moments.

Again, perhaps the development of the human being should be idealized more like a tree than anything else. Ever reaching both up and outward, as well as down and in. Depending on a multitude of factors, some branches may reach more easily that others are more developed in one area than others, and the tree becomes its own unique and lopsided beautiful self. In that way it can be observed that great talent often comes great deficits. The sprouting of ones potential more into one area nearly always results in a drought of others, and likewise the tree that reaches equally in all directions may not reach as high in one. Perhaps we can be good at a lot of things, or simply great at a few, but it is not likely both.

No one ever said this life was without sacrifice.

One of the difficult life lessons for many individuals is that their education is their own responsibility. Truly, no one can teach you what you are not willing to learn. When it comes to ones body, no one can lift the weight, climb the mountain, or even pick ones leg up for them. The intentional study and ownership of ones body and mind is a daily act of ownership.

How one goes about cultivating kinesthetic intelligence will be different for each individual, but its aim should be the same; to inhabit and control ones body in all of its beautiful potential. Although there is no concrete definition of what moving well is, we all can see it clearly when it is both present and absent. Holding in ones mind with respect both ends of the spectrum of human physical capacity gives us both something to strive for and avoid. Truly, this is what exercise is for; it is a practice of a desired skill, movement, ability, repeated over until it comes with ease. Perhaps repeated regularly because it is familiar and one can find flow within it, perhaps repeated because it is a skill we recognize we dearly need to never lose. In that, perhaps, our each and own potentials are all the more so realized.

For more on the crucial component of attention in all this click HERE.

For more on the link between habit and adaptation click HERE.

For more on the effects of our first world lifestyles click HERE.

REFERENCES

- Einarrson-Backes LM, et al “Infant neuromotor assessments: a review and preview of selected interments” Am J Occup Ther 1992 Mar; 46(3):224-32

- Sterberg, RJ “Intelligence” Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012 Mar; 14(1): 19-27

- Aberg, MA “Cardiovascular fitness is associated with cognition in young adulthood” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009 Dec 8;106(49):20906-11

- Hogan CL, et al “Exercise holds immediate benefits for affect and cognition in younger and older adults” Psychol Aging 2013 June; 28(2): 587-594

- Erickson KI, et al “Physical activity, brain, and cognition” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2015 Aug 4:27-32

- Bherer L, et al “A review of the effects of physical activity and exercise on cognitive and brain function in older adults” Journal of Aging Research 2013; 657508

- Ratey JJ, et al “The positive impact of physical activity on cognition during adulthood: a review of underlying mechanisms, evidence and recommendations” Rev Neurosci 2011; 22(2): 171-85

- Gardner, H (1983) Frames of Mind New York: Basic Books

- Gardner H, et al “Multiple Intelligences go to school: Educational implications of the theory of multiple intelligences” Educational Researcher 1989 Nov; 18(9):4-10

- Program for International Student Assessment, http://www.oecd.org

- Eunjung Cha, Ariana “The US recess predicament: Extraordinary photos of what we can learn from play in other parts of the world” Washington Post 2015, Oct 2

- American Academy of Pediatrics “Policy Statement: The Crucial Role of Recess in School” Pediatrics 2013 Jan 131: 1

- Ramstetter CL, et al “The crucial role of recess in schools” J Sch Health 2010;80(11): 517-526

- Barros RM, et al “School recess and group classroom behavior” Pediatrics 2009; 123(2): 431-436

- Jarrett O, et al “Impact of recess on classroom behavior: group effects and individual differences” J Educ Res 1998; 92(2): 121-126

- Pellegrini A, et al “The effects of recess timing on children’s playground and classroom behaviors” Am Educ Res J 1995; 32(4): 845-864

- Alhola P, et al “Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance” Neuropsychiatric Dis Treat 2007 Oct; 3(5): 553-567

- Tolppanen AM, et al “Leisure-time physical activity from mid to late life, body mass index, and risk of dementia” Alzheimers Dementia 2015 Apr; 11(4): 434-443

- Henley J, et al “Robbing elementary students of their childhood: The perils of no child left behind” Education 2007 Fall; 128(1): 56-63

- Johnson, D “Many schools putting and end to child’s play” New York Times 1998, April 7, p. A1

- Duffrin, E “Survey: Recess, gym class short changed” Catalyst Chicago 2005 Oct

- Covey, S “Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” New York, 1989-2004, Simon and Schuster

- Strauss, K “These are the skills bosses say new college grads do not have” Forbes 2016, May 17

- Klonoff, DC “The increasing incidence of Diabetes in the 21st Century” J Diabetes Sci Technol 2009 Jan; 3(1):1-2

- Geiss LS, et al “Increasing Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes – United States and Puerto Rico, 1995-2010” Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2012, Nov 16; 61(45): 918-921